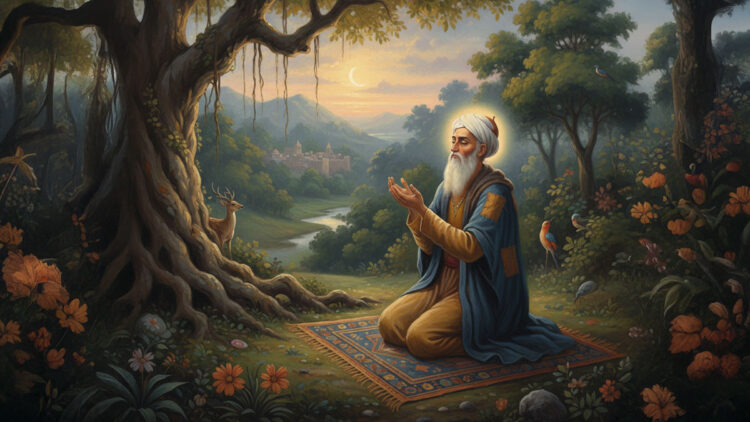

Sufism carries the echoes of nearly fourteen centuries, a long-flowing river of devotion that has shaped the spiritual landscape of the East. Indeed, the Prophet Muhammad, the founder of Islam, is revered by Sufis of all traditions as the first Sufi—the primordial light from which their path emerges. The Prophet’s lifestyle established the foundational archetype for the movement; his integrity, piety, embrace of faqr (spiritual poverty), and absolute submission to the Divine will became the sine qua non for every practitioner.

The Primordial Light: Origins and Early Spread

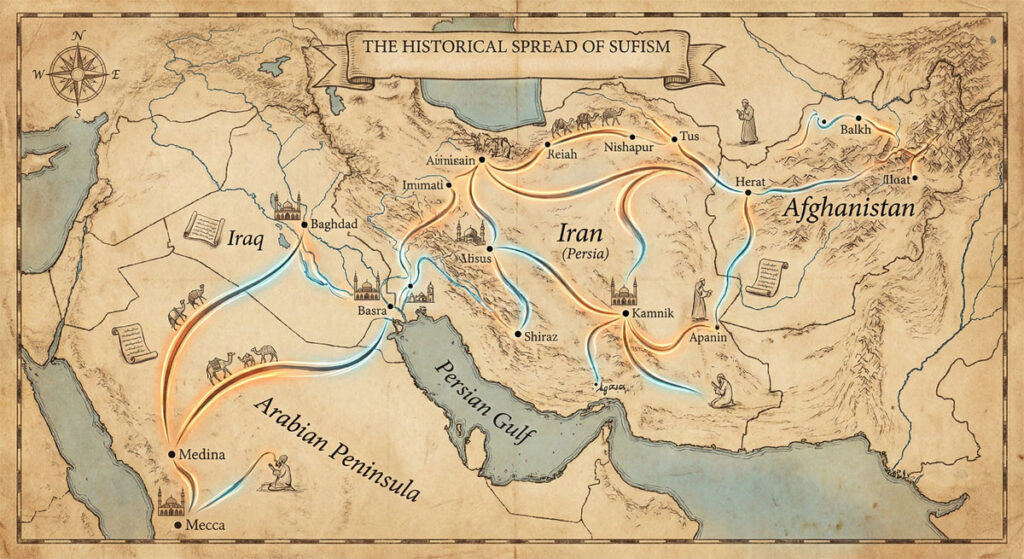

What began as an individual’s internal quest for the Almighty gradually evolved into a widespread movement. From its origins in the Arabian Peninsula, it spread into Iraq and subsequently rooted itself firmly in Northern Iran and Northwestern Afghanistan. While evidence suggests a Sufi presence in India as early as the eighth century, they arrived in significant numbers following the Turkish conquest in the late twelfth century. Over time, they reached nearly every corner of the Subcontinent, leaving an indelible mark on Indian society through their teachings and way of life. Though long deceased, many Indian Sufis remain vibrant in the collective memory of the people. Their shrines stand today as enduring symbols of their legacy, reminding us that the past remains as palpable as the present.

Architects of a Composite Culture

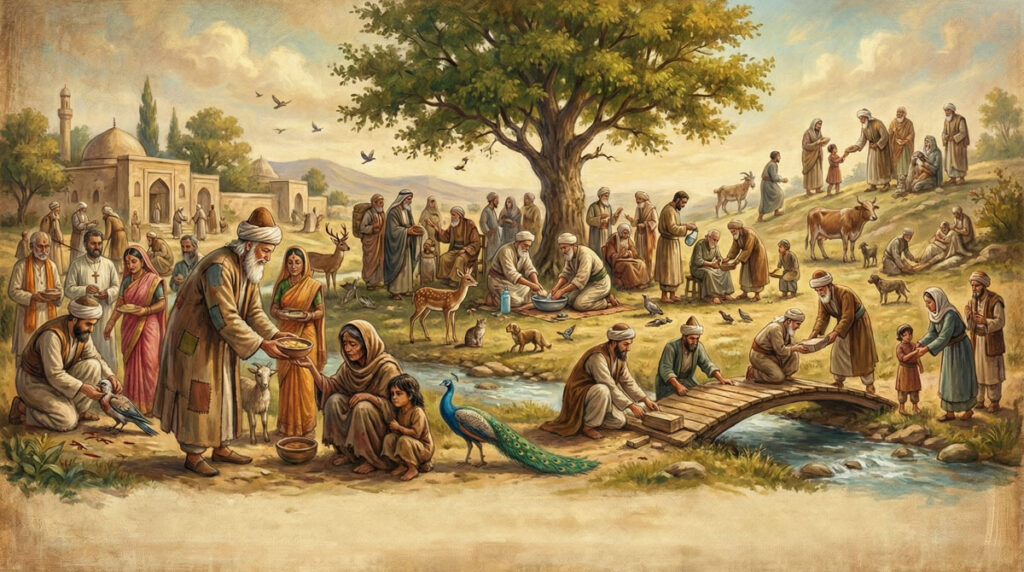

Sufism and Sufis have contributed significantly to the enrichment of the glorious Indian civilization. In fact, it would be no exaggeration to suggest that in the making of India’s composite culture—which is the greatest legacy of medieval India to Indian civilization—the contribution of Sufis has been second to none. By their words and deeds, they helped create an environment in India which was largely free of sectarian and communal tensions. They preferred to communicate in local dialects, welcomed all visitors to their abodes, fed and assisted all those who approached them for succor irrespective of their religious affiliations, respected indigenous cultural traditions, and in the process won the hearts of innumerable followers.

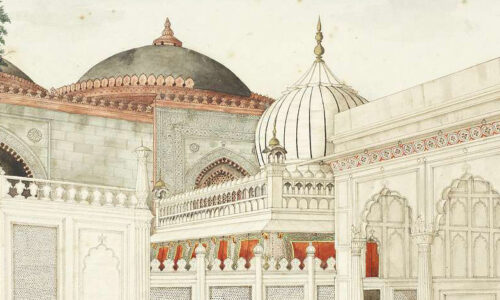

Service to humanity was their motto, and winning the grace of God by showing compassion to His creatures was their objective. The charisma and spiritual prowess of the Sufis, as well as their piety and rectitude, attracted the attention of many members of the ruling class as well. Monarchs and mandarins felt obliged to pay a visit to their humble dwellings and vied with each other in offering landed property and cash stipends to them. They built imposing structures over the graves of the Sufi masters and facilitated the visits of devotees to these shrines. The death anniversaries (Urs) of the Sufis were celebrated with great fanfare, in which rulers and commoners participated with equal zeal and reverence. Reading the collection of discourses (malfuzat) of the Sufi masters became the favorite pastime of the educated and the learned.

The Conflict of Doctrine: Sufis vs. Theologians

Notwithstanding its immense popular appeal, there was no dearth of detractors of the Sufis and Sufism. Right from its inception, the theologians (Ulama) were at the throats of the Sufis. They criticized many of the practices and beliefs associated with Sufism and went to the extent of denouncing it as something alien to Islam. The ecstatic utterances of some of the early Sufis, such as Bayazid Bistami (d. 874) and Mansur Hallaj (d. 922), did not help the cause of Sufism either and provided ready ammunition for the theologians to castigate the movement.

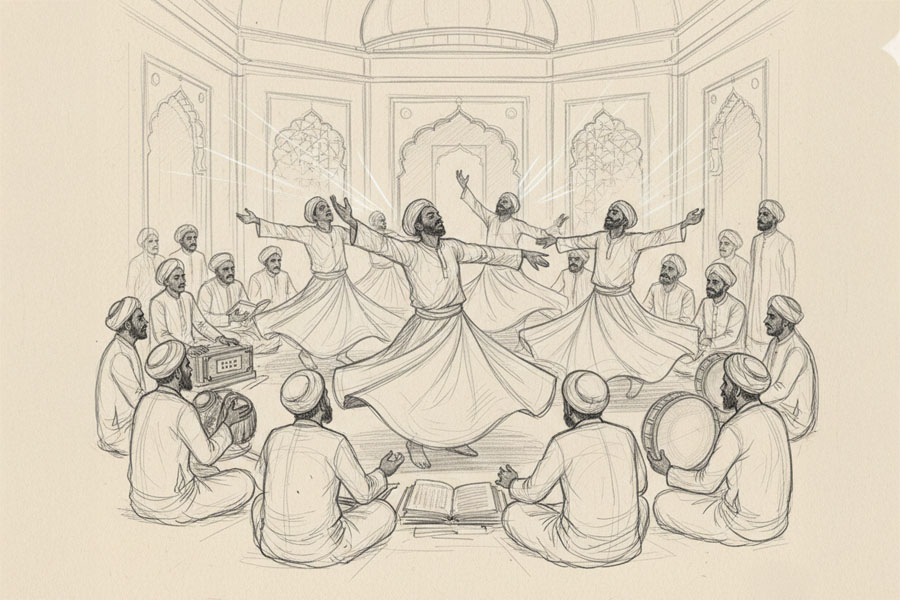

Sama’ and the Evolution of Qawwali

They organized massive propaganda against Sufi practices, especially Sufi music known in popular parlance as sama’. Literally meaning “audition” or “listening,” sama’ was originally a kind of concert characterized by the recitation of the divine names and religious poetry—in praise of Prophet Muhammad or Sufi masters—that might or might not be accompanied by musical instruments. The theologians rejected the claim of the Sufis that sama’ was a source of spiritual ecstasy or a divine inspiration that ignited the spark of celestial love in the heart of the participant; instead, they denounced it as a gross violation of Islamic law (Shariat).

Despite the vociferous hue and cry raised by the theologians, sama’ remained part and parcel of Sufi life and culture. A modern parallel or counterpart of sama’ is qawwali. An Arabic word meaning “recited,” qawwali is a regular feature of Sufi gatherings at the shrines belonging to the Sufis of the Chishti order nowadays. The popularity of qawwali music has not remained confined within the four walls of Sufi shrines. It has found a large audience at the level of popular culture, cutting across religious, linguistic, and geographical boundaries; indeed, many qawwali performers, such as Habib Wali Muhammad, the Sabri Brothers, and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, have become household names in India and abroad.

Contemporary Skepticism and Enduring Charisma

Many modern Muslims, however, continue to be skeptical about the true character of Sufism. They believe that Sufism has been derived from the idolatrous practices of saint-worshipping Christians and the heretical doctrines of pantheistic Greek philosophers. They see in it such “abominations” as the worship of tombs, pagan music borrowed from Hindus, and the fleecing of credulous believers by greedy and fraudulent Sufi masters1. Many more look upon the Sufis as violators of Islamic law and abjurers of Islamic rituals.

Yet, the ground reality is entirely different. The crowds of devotees and the high-profile visits of popular Bollywood actors and powerful politicians to Sufi shrines—located in practically every nook and corner of the Subcontinent—tell a different story. These sights lead the onlooker to ponder the antecedents of the Sufis, the secret of their popularity among both high and low, Hindus and Muslims, and the mystery of their enduring charisma centuries after their demise. Some of these questions are addressed in the present essay.

Ultimately, the enduring influence of Sufism lies in its ability to transcend the rigid boundaries of time and doctrine. While theological debates and modern skepticism persist, the visceral reality of the shrine—filled with the scent of rose petals and the sound of the qawwal—testifies to a spiritual hunger that refuses to be silenced. In the quiet presence of these masters, the historical and the contemporary merge, proving that their message of compassion and divine proximity remains as vital to the fabric of the Subcontinent today as it was seven centuries ago.

To be continued…

- Carl W. Ernst, Sufism, Shambhala South Asia Editions, New Delhi, 2000, xii ↩︎