In this second installment of our series, we shift our focus from the broad origins of Sufism to its specific flowering within the Indian Subcontinent. As Delhi rose as a preeminent center of political power, it simultaneously became the “Threshold of the Saints,” a spiritual sanctuary for those fleeing upheaval and seeking the Divine. Here, we explore the arrival of the great orders and the resilient scholars who kept the flame of spiritualism alive through centuries of transition.

The Migration of the Mystics

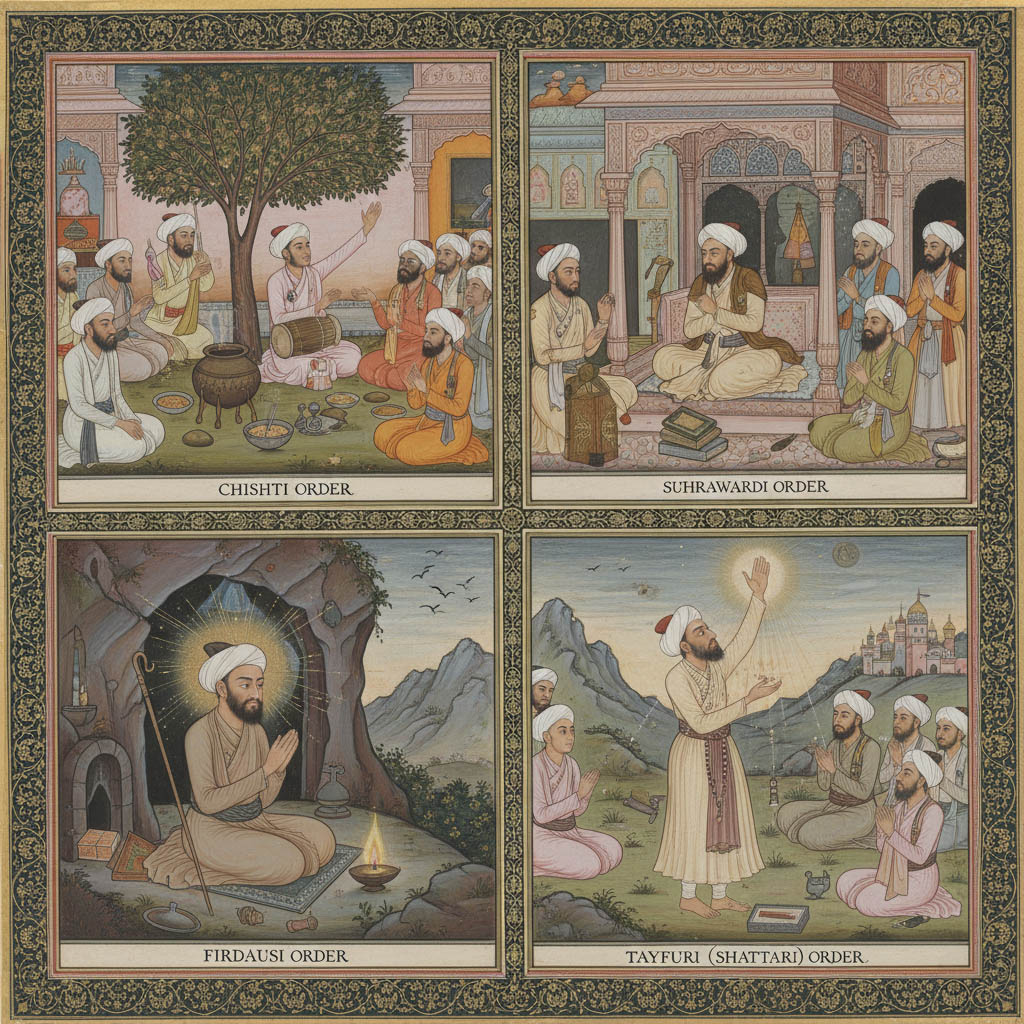

As mentioned earlier, the Turkish conquest of Northern India in the late twelfth century stimulated a large-scale migration of Sufis from all parts of the Muslim world to the Subcontinent. Three centuries later, Abul Fazl found fourteen Sufi khanwadas (families or orders) flourishing in India1. None of the fourteen orders mentioned by Abul Fazl originated in India, and only four—the Chishti, the Suhrawardi, the Firdausi, and the Tayfuri (also known as Shattari)—were able to exercise substantial influence on the life and thought of the Indian people in the medieval period.

These were by no means the only Sufi sects active in India; Sufis of the Madari, Qadiri, and Naqshbandi orders, to name a few, had also appeared. Each of these orders rallied around prominent adherents who quickly carved out their walayats (spiritual territories) and established elaborate networks of Khanqahs (hospices), khalifas (spiritual successors), and khadims (disciples or servitors) across the Subcontinent. This network helped create a wider constituency for the founders and facilitated the transmission of their messages, diffusing tales of spiritual charisma and prowess to far-flung areas. The shrines of these saints later became the most important centers of pilgrimage for the devotees associated with those orders.

Delhi: A Sanctuary from the Mongol Onslaught

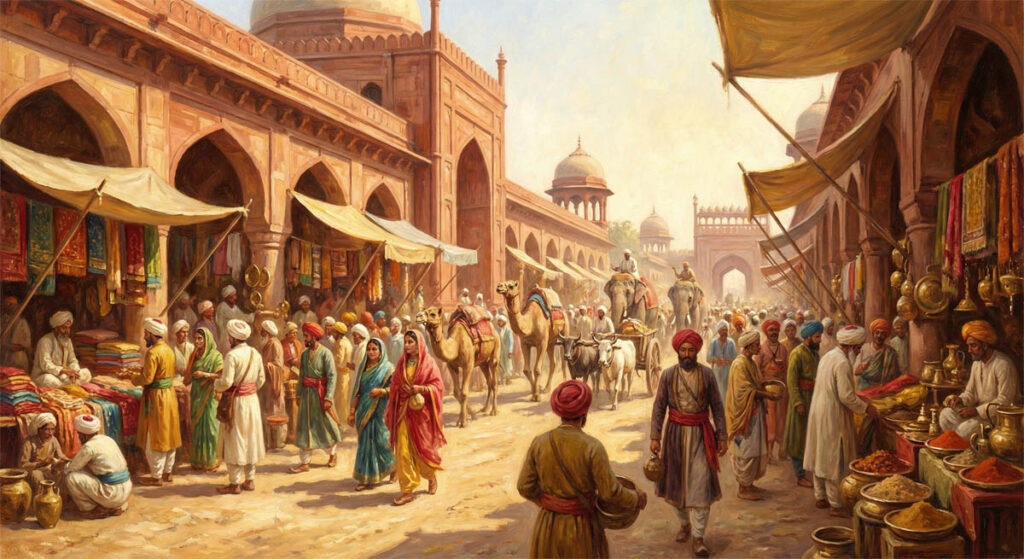

Many of these Sufi masters migrated from distant regions and settled in Delhi—the seat of the Delhi Sultanate. The causes of their migration are easily identified. In the thirteenth century, the Delhi Sultanate emerged as the sole place of refuge where Muslims of Central and Western Asia, suffering from the devastating consequences of the Mongol onslaught, could find succor and a safe haven.

Writing as early as 1260, the Sultanate historian Minhaj-i Siraj Juzjani observed that during the reign of Sultan Shamsuddin Iltutmish (r. 1210–36), “the kingdom of Hindustan, by the grace of Almighty God… became the focus of the people of Islam and the orbit of the possessors of religion”2. Ninety years later, another historian, Isami, asserted that during the same reign, “Craftsmen of every kind and every country as well as beauties from every race and city; many assayers, jewelers and pearl sellers, philosophers and physicians of the Greek school and learned men from every land – all gathered in that blessed city [Delhi] like moths that gather round the candle light. Delhi became the Ka’ba of the seven continents and the whole region became the home of Islam”3. The magnificence of the city continued to grow even after the Sultan’s demise. Ibn Battuta, who visited during the reign of Sultan Muhammad Tughluq (r. 1325–1351), described it as one of the greatest cities in the world4. It is little wonder that masters of the stature of Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki (d. 1235), Nizamuddin Auliya (d. 1325), and Nasiruddin Chiragh-i Delhi (d. 1356)—all belonging to the celebrated Chishti order—chose to reside in Hazrat-i Delhi, as the city came to be known.

Spiritual Resilience in Times of Instability

By the turn of the fifteenth century, however, Delhi had passed practically into a spiritual wilderness. The departure of the last great Chishti saint of the metropolis, Saiyid Muhammad Yusuf Husaini Gesudaraz (d. 1422), to the Deccan following Timur’s invasion (1398), the subsequent collapse of the Tughluq dynasty, and the transfer of the capital to Agra by Sikandar Lodi (1504) obliged many stalwarts to migrate.

It does not, however, mean that Delhi had become completely bereft of Sufis in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Many lesser-known Chishtis continued to provide guidance to the seekers of the truth in the city. Sheikhs Hasan Tahir (d. 1503), Muhammad Hasan (d. 1537), Abdur Razzaq Jhinjhana (d. 1544), Amanullah Panipati (d. 1550), Qazi Khan (d. 1560), Abdul Aziz bin Hasan Tahir (d. 1567), Chain Laddah (d. 1590), Abdul Ghani (d. 1599), and many equally distinguished Sufis kept the flame of spiritualism alive in the capital of the Sultans. Almost all these Sufis were enthusiastic advocates of the doctrine Wahdat al-wujud (Unity of Being)5. They gave popular lectures explaining the doctrine and wrote influential treatises in its support. Sheikh Chain Laddah even figured prominently in Akbar’s Ibadat Khana assemblies in Fatehpur Sikri. Abdul Qadir Badauni has accused the Sheikh of departing from the time-honored Chishti traditions and succumbing to the lure of the comforts of court life6.

The Naqshbandi Horizon: Khwaja Baqi Billah

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Sufis of the Naqshbandi order shone brightly on the spiritual horizon of Delhi. The credit for establishing the Naqshbandi order on a firm footing in Delhi is generally given to Khwaja Baqi Billah (d. 1603). A native of Kabul and Khalifa of the famous saint Khwajgi Amkingi (d. 1598), Khwaja Baqi migrated to India at the advice of his pir (spiritual preceptor) and settled in Delhi, where he died in 1603 after a short but extremely fruitful spiritual career. Like most Naqshbandis, he was an ardent spokesman of Wahdat al-wujud and composed inspiring verses elucidating his passion for the doctrine. He suggested that the attainment of mystic perfection was impossible without a clear perception of Wahdat al-wujud7. The Khwaja also practiced sama’ and regarded it as a source of spiritual solace for the Sufis8. He made efforts for the unhindered enforcement of the Shariat in the Mughal dominions and corresponded regularly with the leading Mughal nobles of his time, urging them to serve the cause of Islam.

Khwaja Baqi’s successor in Delhi and also the custodian of his khanqah (hospice) in the city was Khwaja Husamuddin (d. 1633). He was a senior Mughal noble and an important member of Abdur Rahim Khan-i Khanan’s entourage in the Deccan. Frustrated by the protracted warfare in the Deccan, Husamuddin resigned his military commission and traveled to Delhi, where he met Khwaja Baqi and became his disciple. Husamuddin’s devotion for his master was proverbial. Throughout his life, he paid daily visits to the Khwaja’s tomb and spent several hours there. He also brought up Khwaja Baqi’s sons with great affection9. Like his master, he was a Wujudi, but there is little evidence of his interest in sama’.

Reform and Rival Doctrines: Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi

Perhaps the greatest Naqshbandi saint of the seventeenth century was Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi (d. 1624). Although he did not live in Delhi and propagated the order from his native town, Sirhind, he maintained intimate relations with the Naqshbandi Sufis of Delhi. Sheikh Ahmad is better known for spearheading a campaign for reforming Indian Islam, which won him the title of Mujaddid Alf-i Sani (Reformer of the second millennium). He is also known for popularizing the doctrine of Wahdat al-shuhud in contradistinction to the doctrine of Wahdat al-wujud10. He also established an elaborate network of disciples and Khalifas which, according to the Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–1627), were active in practically every town and city of the Mughal Empire11.

Khwaja Abdullah, alias Khwaja Khurd (d. 1664), son of Khwaja Baqi, was his leading Khalifa in Delhi. Contrary to his master, the Khwaja espoused the cause of Wahdat al-wujud and asserted that the doctrine and the Shariat were two sides of the same coin. Another prominent Naqshbandi Sufi of Delhi who, like Khwaja Khurd, moved away from the Mujaddidi mystic tradition by advocating Wahdat al-wujud was Shah Abdur Rahim (d. 1719). He believed that the doctrine was based on sound logical considerations and could be explained convincingly from the testimony of the Quran and the Hadith (traditions of the Prophet Muhammad). Contrary to the Naqshbandi traditions, he also refused to align himself with the state. He declined to serve on the board of scholars appointed by Emperor Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707) to review the Emperor’s favorite project, Fatawa-i Alamgiri, and in spite of repeated requests by the Emperor, did not pay a visit to his court12.

Shah Waliullah: The Bridge Between Eras

Shah Waliullah (d. 1762) was the leading Naqshbandi saint of Delhi in the eighteenth century. Son of Shah Abdur Rahim and educated in Delhi and the Hijaz, Waliullah has been hailed as the bridge between medieval and modern Islam in India13. He was painfully conscious of the corruption and laxity that prevailed in the religious and moral life of his co-religionists. The moral turpitude of the Muslim religious and intellectual elites of his day also hung heavier on his soul than it did on the average Muslim who was content to let things happen and had practically no inclination toward introspection or moral reasoning. He was convinced that the only way of taking the Muslims out of the abyss of misguided religious innovation and moral decadence was to make them aware of the true import of the teaching of the Quran and the Hadith.

Precisely for this reason, he translated the Quran into Persian (1737–38). Although the Indian Muslim intelligentsia did not welcome this rendering of the “word of God” into the language of the people, Shah Waliullah remained committed to the cause of Muslim reform throughout his life. In his last testament, he directed the attention of his fellow Muslims to the social evils plaguing their society. The prohibition of widow remarriage, expensive ceremonies associated with marriage and death that most Muslims could ill afford, and the practice of fixing exorbitant mahr (dower money), he said, did not exist in Arabia. They have their source, he asserted, in a non-Muslim ethos and need to be abandoned14.

Sir Muhammad Iqbal writes that Shah Waliullah was the first Indian Muslim “who felt the urge of the new spirit in him”15. Indeed, his open-minded, moderate, and catholic approach to all religious and theological disputes of his day paved the way for new thinking in many spheres and has hardly a parallel in the history of Indian Islam. His approach to Sufism was likewise cosmopolitan. Though a Naqshbandi by initiation, he took inspiration from all the four principal Sufi sects of his time. In fact, at the time of initiating novices to his circle of disciples, he used to refer to the prominent saints of each of the four sects with a view to attracting their spiritual bliss to the novice. His stand on what came to be known as gor-parasti (worship of the shrines of the saints) was in the same measure judicious. He decried the practice of seeking material help from the dead saints but did not prohibit visits to their shrines altogether. In moments of need, he would himself visit the grave of his father for succour16. Shah Waliullah also strove to reconcile the doctrines of Wahdat al-wujud and Wahdat al-shuhud. In his treatise Risala-i Wahdat al-wujud wa al-shuhud, he suggested that the two doctrines represent two paths leading to the same goal17.

Mirza Mazhar Jan-i Janan: A Pluralistic Vision

A junior contemporary of Shah Waliullah was Mirza Mazhar Jan-i Janan (d. 1781). Born into a family of Mughal military elites, Mirza Mazhar was educated at Delhi and at the young age of sixteen was initiated into the Naqshbandi order by the renowned Sufi Nur Muhammad Baduni (d. 1723). Mirza Mazhar lived in Delhi at a time of intense political and social upheaval in the city. The capital of the Mughal Empire was plundered by Nadir Shah before his very eyes (1739). The subsequent emergence of diverse claimants to the political power and wealth of Delhi—including the Afghans, Sikhs, Jats, and Marathas—and their repeated depredation of the city and its suburbs left a deep impact on his mind and thought.

The decline of Muslim political power was accompanied by a deepening crisis in the social and moral fabric of the Muslim community. He worked hard to eradicate the innovations that had crept into Indian Islam of his day and led by example by strictly adhering to the teachings of the Quran and Hadith. Like Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi, he sent his disciples to practically every part of India to popularize not only the practices of the Naqshbandi order but also to remind the Muslims of their duties toward God and the Prophet. He kept his disciples on a tight leash, constantly reminded them to strictly adhere to the Shariat, and visited them periodically to supervise their activities from close quarters18.

Mirza Mazhar’s approach to Hindu religious thought, rituals, and scriptures was distinctly conciliatory and sympathetic. In a letter written in 1750 in response to a disciple’s query regarding the normative validity of Hinduism, Mirza Mazhar, while asserting the superiority of Islam over all other existing religions of his time including Hinduism, presents “Hinduism as a perfectly monotheistic tradition that contained clear doctrines regarding rewards and punishments in the hereafter, and that explicitly acknowledged the existence of prophets and angels”19. He not only affirmed the divine origin of the Vedas but also equated Dharmasastra and Karmasastra with ilm al-kalam (dialectical theology) and ilm-i fiqh (jurisprudence) respectively.

What is more interesting is that he makes a clear distinction between the idol worship of the pre-Islamic Arabs and the idol worship of the ahl-i Hind (Hindus). The idol worship of the former, he asserts, involved shirk (polytheism) simply because they believed in the divinity of their idols, which is tantamount to the association of partners with God. The Hindus, on the other hand, use idols as a source of meditation in order to establish a spiritual bond with the figure represented by the idols, enabling them to fulfill their mundane as well as religious needs, which cannot be regarded as shirk. This was not all. The saint further averred that the Hindu ritual, in fact, resembles the Sufi practice of tassawur-i Sheikh, by which the Sufis focus on the person of their spiritual masters in the state of meditation and acquire spiritual solace in the process. Mirza Mazhar also reminded the addressee that God had sent His messengers to India also, even though their names have not been mentioned in the Quran, and quotes several Quranic verses in support of his contention20.

The Seal of the Saints and the Urdu Tradition

Mirza Mazhar’s principal Khalifa and his spiritual successor was Shah Ghulam Ali (d. 1824). Known as Khatam al-aulia (seal of the saints), Shah Ghulam Ali had his initial education in Batala (Punjab) but later migrated to Delhi, where he joined the circle of Mirza Mazhar Jan-i Janan at the age of twenty-two. Sir Saiyid Ahmad Khan (1817–1898) had seen Shah Ghulam Ali from close quarters in his childhood and has given a detailed description of the Shah’s personality traits and his immense popularity among the people at large. Seekers of truth from all parts of India and abroad, we are told, flocked to his khanqah in Delhi. He trained innumerable disciples, but his greatest service to Indian Sufism was to popularize the Mujaddidi branch of the Naqshbandi order in Central Asia and the Middle East. For instance, his foremost Khalifa, Maulana Khalid Kurdi (d. 1827), spread the order in the Ottoman territories. The Maulana had a large number of followers who contributed substantially to spreading the order in West Asia. Many Naqshbandi Sufis active in Turkey and the adjoining countries in our own time trace their spiritual descent from him21.

A famous contemporary of Shah Ghulam Ali, albeit perhaps not as distinguished, was Khwaja Mir Dard (d. 1785). Better known today as a poet of Urdu and Persian and perhaps the first to write mystical verses in Urdu, Mir Dard was educated under the watchful eyes of his father, Khwaja Nasir Andalib (d. 1759). Much of his writing conveys his deep sense of anguish over the political, social, and religious malaise that afflicted the Muslim society of his time. He spoke against the raging controversy between the supporters of the doctrines of Wahdat al-wujud and Wahdat al-shuhud, which had practically divided the Muslim community into two warring groups. He believed that the conflict was futile, for the sum and substance of both doctrines “is to disassociate the heart from things other than God and to depend entirely on God because the culmination of tauhid-i wujudi is in shuhud“22.

He was convinced that instead of wasting their time on debating controversial issues endlessly, Muslims should take inspiration exclusively from the teachings of the Quran and the precepts of the Prophet Muhammad. Precisely for this reason, he tried to propagate the tariqah-i Muhammadiya, which his father had established. This tariqah, claimed Mir Dard, furnishes the best way that enables the salik (seeker of the truth) to reach his coveted destination, for it is the pure Islamic way—the path laid down by the Prophet Muhammad 1100 years ago. The sect, however, failed to attract the attention of the masses and remained, at best, a family affair of its founder23.

The story of Sufism in Delhi is not merely one of individual piety, but of a profound cultural synthesis that weathered political storms and social shifts. From the early Chishti masters to the reformist zeal of the Naqshbandis, these figures ensured that Delhi remained a sanctuary of the soul. Their ability to bridge the gap between the ruling elite and the common folk, and between different religious traditions, created a legacy of pluralism that defines the city to this day.

To be continued…

- Abul Fazl, Ain-i Akbari, (trans.), H. S. Jarrett, 1893-96, rpt, New Delhi, 1978, vol. iii, 393 ↩︎

- Minhaj-I Siraj Juzjani, Tabaqat-i Nasiri, (trans.), H. G. Raverty, 1881, rpt, Delhi, 1970, vol. ii, 642 ↩︎

- Isami, Futuh’s Salatin, (trans.), Agha Mehdi Husain, London, vol. ii, 227 ↩︎

- Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta, The Rehla, (trans.), Agha Mehdi Husain, 1953, rpt, Baroda, 1976, 24 ↩︎

- The doctrine of Wahdat al-wujud was propounded by the Spanish Sufi Muhiuddin Ibn Arabi (d.1241). It envisaged the identity of the Zat (Being) and Sifat (attributes of God). According to Ibn Arabi, Being is one; everything else is His manifestation. The universe is thus nothing but the manifestation of God’s attributes. The universe in other words is a mode of God; apart from God it has no existence. Ibn Arabi also claimed that God’s attributes are also manifested in man. God created man in His own image. God and man, Haqq and khalq are therefore identical. The doctrine, in a nutshell, affirms that God alone exists, and other than God, nothing exists(there is nothing but God, nothing in existence other than he). The doctrine had a deep and lasting influence on Indian Sufism. Although there is no reference to the doctrine in the malfuzat (collection of discourses) of Sheikhs Nizamuddin and Nasiruddin, it had gained wide currency in India by the turn of the sixteenth century. In the formation of Akbar’s policy of Sulh-i Kull (universal / absolute peace) as also in the development of Akbar’s worldview, the influence of Wahdat al-wujud is clearly perceptible. ↩︎

- N. R. Farooqi, Medieval India: Essays on Sufism, diplomacy and History, Allahabad, 2006, 141 ↩︎

- Malfuzat-i Khwaja Baqi Billah, f 13a, quoted by S. A. A. Rizvi, History of Sufism in India, New Delhi, 1983, vol..ii, 190 ↩︎

- Khwaja Muhammad Kishmi, Zubdat al-maqamat (trans.), Ghulam Mustafa Khan, Sialkot, 1986, 95 ↩︎

- Zubdat al-maqamat, 124-26 ↩︎

- The doctrine of Wahdat al-shuhud was originally propounded by the Irani Sufi Alauddaulah Simnani (d.1336). Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi used and elaborated it in order to blunt the rising influence of Wahdat al-wujud on Indian Sufis. He asserted that the identity of Haqq and khalq is phenomenal and far from real. He asserted that Wahdat al-wujud represented the first and therefore immature state of Sahw (sobriety) where the seeker believing in the identity of the Creator and created denies the plural manifestation of God’s attributes and regards everything as non-existent. Wahdat al-shuhud on the other hand represents the final or mature state of Sahw where the seeker perceives the phenomenal nature of this unity which enables him to recognize the separate existence of God and His attributes. See Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi, Maktubat-i Imam-i Rabbani, (ed.), Nur Ahmad Amritsari, Istanbul, 1977, vol. I, 222-32, 257-58, 263-67; vol. ii, 5-13, 118-24. Also see Burhan Ahmad Faruqi, Mujaddid’s Conception of Tauhid, Delhi, 1940, 117-39; Y. Friedman, Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi: An outline of His Thought and a Study of His image in the Eyes of Posterity, Montreal and London, 59-60 ↩︎

- Nuruddin Muhammad Jahangir, Tuzuk-i Jahangiri, (trans.), A. Rogers and H. Beveridge, rpt, Delhi, 1968, vol. ii, 91-2 ↩︎

- Shah Waliullah, Anfas al-arifin, (trans.), Hakim Muhammad Asghar, Lahore, n.d., 19-140 ↩︎

- Aziz Ahmad, Studies in Islamic Culture in the Indian Environment, 1964, rpt. Delhi, 2000, 201 ↩︎

- S. M. Ikram, Rud-i Kausar, 1957, rpt. Delhi, 1991, 571-73 ↩︎

- Muhammad Iqbal, Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, London, 1934, 162 ↩︎

- J. M. S. Baljon, ‘Shah Waliullah and the Dargah’, in Christian W. Troll, Muslim Shrines in India, delhi, 1989, 192-97 ↩︎

- S. M. Ikram, Rud-i Kausar, 563-67 ↩︎

- Muhammad Umar, Islam in Northern India During the Eighteenth Century, Delhi, 1993, 70-87. Also see S. Moinul Haq, Islamic Thought and Movements in the Subcontinent (711-1947), Karachi, 1979, 372-378. For a detailed account of the life and times of Mirza Mazhar Jan-i Janan see Shah Ghulam Ali, Maqamat-i Mazhari, Delhi, 1892. Also see Abul Khair Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Muradabadi, (ed.) Kalimat-i Taiyibat, Muradabad, 1891; Khaliq Anjum, (trans.), Mirza Mazhar Jan-i Janan ke Khutut, Delhi, 1962 ↩︎

- Sher Ali Tareen, ‘Reifying Religion while lost in Translation: Mirza Mazhar Jan-i Janan on the Hindus’, Macalester Islam Journal, vol. 1, no. 2, 2006, 45. Also see Y. Friedmann, ‘Islamic Thought in Relation to the Indian Context’ in Richard M. Eaton (ed.), India’s Islamic Traditions, 711 – 1750, Oxford India Paperbacks, New Delhi, 2006, 58-9; Y. Friedmann, ‘Medieval Muslim Views of Indian religions’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 95, 1975, 217-21 ↩︎

- Ibid, 48-51. Also see S. M. Ikram, Rud-i Kausar, 646-49; Muhammad Umar, Islam in Northern India During the Eighteenth Century, 526-27 ↩︎

- Ibid, 87-91. Also see S. M. Ikram, Rud-i Kausar, 651-57 ; Sir Saiyid Ahmad Khan, Asar al-sanadid, 1847, rpt. Delhi, 1965, 461-69 ↩︎

- Muhammad Umar, Islam in India in the Eighteenth Century, 123 ↩︎

- Ibid, 91-101. Also see A. D. Nasim, ‘Khwaja Mir Dard ka Khandan’, Oriental College Magazine, 1958, 136-59 ↩︎