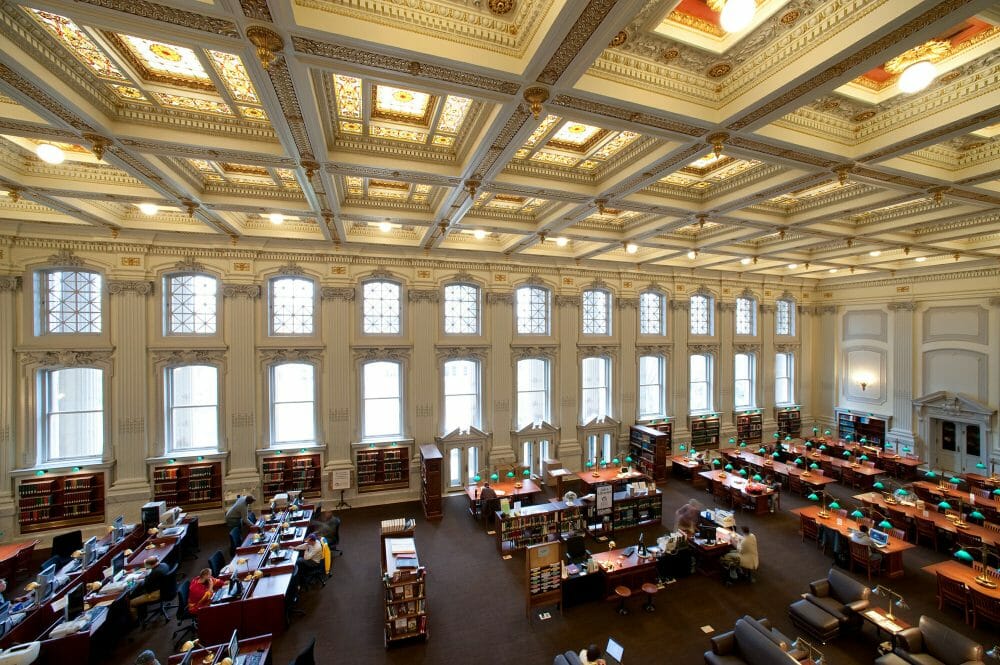

In the last part of my story, I shared how I was promoted to a permanent lecturer position at the University of Allahabad, a significant professional milestone. I also recounted some wonderful personal moments: my marriage to Nilofer, the birth of our son, Tipu, and the incredible opportunity that led me to accept a Fulbright Junior Fellowship for graduate studies in the USA. Now, I pick up the narrative in September 1978, as I navigate my first academic steps at the prestigious University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Navigating Graduate Studies in Madison

The first semester at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, which began in the first week of September, was challenging. I enrolled in three demanding courses: two at the 800 level and one at the 400 level. Professor Norman Risjord taught the first course on Early American History, while Professor Frykenberg taught the other two on Modern and Early Modern History. For each course, we were required to write a term paper and take a final examination. Professor Risjord assigned me to write a paper on the Monroe Doctrine, and Professor Frykenberg had me tackle the East India Company’s Revenue Administration in the Shahabad district of Bihar for the 800-level course, and the personality and policies of Muhammad Tughluq for the 400-level course. I worked incredibly hard on both the term papers and the final examinations. At the end of the semester, I received an AB in Professor Risjord’s course and an A in both courses offered by Professor Frykenberg. These excellent grades were more than enough to fulfill the required grade point average for graduate students.

The weather in Madison was much harsher than I had anticipated. Snowfall started in early October, and the average temperature was consistently below 20∘ Celsius. Although my apartment and the entire university had central heating, I quickly had to buy extra warm clothes and snow boots for traveling to the university and the market.

I was fortunate to quickly make friends with many Indian students who lived in the Saxony Apartment or nearby. I frequently met with Abdullah Badshah, Tahsin Siddiqui, Reazul Haq, and Acharya to discuss my studies and problems. Professor Memon, my brother’s friend, was also incredibly kind, inviting me to his home for lunch on weekends. My cousin, Saeed Farooqi, and his wife Farzana, who lived in the nearby town of Davenport, Iowa, even visited one weekend and brought me homemade food—a gesture I was truly grateful for. I prepared my morning tea, breakfast, and meals in the common kitchen on my floor, which I shared with other residents of the apartment.

The Path to the Ph.D. Program

By the end of the first semester, I had made a very positive impression on Professor Frykenberg, and he advised me to get enrolled in the Ph.D. program. There was a complication, however: the university did not recognize M.A. degrees from foreign countries, meaning students were typically required to earn a Master’s degree at Wisconsin before applying for the Ph.D. program. Professor Frykenberg wrote a strong letter to the Dean, arguing that this requirement should be waived in my case. He highlighted the academic reputation of Allahabad University and the significant contribution of the Allahabad School of History to historical knowledge, with which I had been associated as a faculty member for six years.

The Dean finally accepted Professor Frykenberg’s recommendation, and by the end of the second semester, I was allowed to enroll directly in the doctoral program. Furthermore, Professor Karpat very kindly promised to arrange a fellowship from the Department of International Studies to cover my tuition and other expenses for the next two semesters. The University also graciously allowed me to take up a campus job to manage my daily expenses.

In the second semester, I took three more 800-level courses with Professor A.K. Narayan, Professor Frykenberg, and Professor Paul Conklin (in American History). I again secured an A grade in the courses taught by Professors Narayan and Frykenberg and an AB in Professor Conklin’s course. My consistent, high grades in the second semester were certainly a great help in securing the fellowship from the Department of International Studies.

Family Reunion in Madison

During my first two semesters, I was diligently saving money to facilitate the arrival of Nilofer and Tipu in Madison. When I went to the Foreign Students Advisor’s office, I was told I needed to show a bank balance of $1,000 to obtain the necessary papers for their U.S. visas. I only had $600 in my account. Fortunately, my friend Acharya came to my rescue, lending me the remaining $400, which I immediately deposited and used to get the required bank statement. After several weeks and frequent visits to the office, I finally received the papers for the J-2 visa for Nilofer and Tipu, which they would need to present at the American Embassy in New Delhi.

In the meantime, I had started working in the microfilming section of the University library in the afternoons, where I was paid $4.50 per hour for four hours each weekday. After some time, I saved enough money to buy round-trip air tickets (New Delhi–London–Chicago on a British Airways flight) for Nilofer and Tipu, which cost $990. I mailed the visa papers and the tickets to Nilofer. Once again, my brother Bhaiya was kind enough to assist Nilofer and Tipu with the visa process and made all the necessary arrangements for their flight to Chicago.

I had also applied for a two-bedroom apartment in the Students Housing Colony, Eagle Heights, located on the bank of Lake Mendota. I was quickly allotted house number 604-D at a monthly rent of $180. With the help of my friends and Professor Memon, I bought the necessary secondhand furniture. In May 1979, Nilofer and Tipu flew from New Delhi, and I went to receive them at the Chicago airport in the car of an elderly classmate, Ms. Alice Findlay. I brought them back to our new apartment in Eagle Heights.

The arrival of Nilofer and Tipu was one of the happiest moments of my entire time in Madison. Nilofer immediately took charge of the household duties and ensured all my needs were met, allowing me to focus completely on my studies. Tipu was a happy child who quickly recognized me and would run into my arms whenever I returned from the university. Our social circle also expanded rapidly. My Indian friends—Abdullah Badshah, Tahsin Siddiqui, Acharya, Yaqoob saheb, and Muhammad Amin—were regular visitors. We also became very friendly with Amanullah Khan saheb and Chaudhary Ghaffar, both from Lahore, and their families.

Deepening the Research

In the third semester, Professor Karpat advised me to take a course on the Turkish language and an 800-level course on Ottoman History. Professor Frykenberg insisted I take a 700-level course, which was mandatory for all graduate students, offered by Professor Jan Vansina on History and Theory. Professor Vansina was the world’s leading authority on Oral History, and I learned a great deal from him, especially about classroom teaching techniques. He asked me to present a paper on the oral tradition in Islam: the traditions of Prophet Muhammad. I consulted a large number of books on the Prophetic Traditions (the Hadith) for this paper. Professor Vansina was very impressed with my presentation and went out of his way to praise me to Professor Frykenberg. I was delighted to receive A grades in all my courses that semester. My term papers for Professors Karpat and Vansina were typed by Nilofer on the electric typewriter loaned to us by our Chinese neighbor, which helped me save a significant amount of money.

In the fourth semester, I continued with 800-level courses from Professors Karpat and Frykenberg and a 500-level course in advanced Turkish language taught by Dr. Sarah Atish. The department chairman advised me to begin preparations for the preliminary examination at the end of the fourth semester, which was required for my formal enrollment in the Ph.D. program. Professor Frykenberg was formally appointed as my research supervisor. Graduate students were given only two chances to clear this preliminary examination; failure to do so meant they would only be awarded an M.A. degree and denied enrollment in the Ph.D. program.

Professor Karpat suggested I write a research proposal on Mughal–Ottoman Relations, a field that was, until then, totally unexplored. Professor Frykenberg agreed and encouraged me to write the proposal with great care and diligence. I worked hard on the proposal, which was titled: Mughal–Ottoman Relations: A Study of Political and Diplomatic Relations between Mughal India and the Ottoman Empire in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. I successfully defended the proposal before a five-member committee of professors, enduring a thorough grilling from each member.

At the end of the fourth semester, the department advised me to take the preliminary examination. It was a take-home examination consisting of four questions set by Professors Frykenberg, Narayan, and Karpat, with a one-week deadline for submission. As usual, I worked tirelessly to prepare. Nilofer typed the four lengthy essays on the electric typewriter and submitted them to the department before the deadline. About a week later, Professor Frykenberg called me with the happy news: I had passed the preliminary examination! I was overwhelmed with joy, as this completed all the formalities for my official enrollment in the Ph.D. program.

On the Road to Research

With my Ph.D. status secured, the next logical step was field research. Professor Karpat advised me to go to Turkey. He was gracious enough to contact his friend, Mr. Ahmad Aydin Bolak, the Director of Turk Petrol in Istanbul, to sponsor my visit. Mr. Bolak agreed to award me a monthly fellowship of 40,000 Turkish liras for three months to support my expenses while conducting research in the Turkish National Archives in Istanbul. He sent a letter confirming the sponsorship.

I still needed to arrange the airfare to Istanbul myself. I used all my savings to buy tickets for all three of us on Turkish Airlines. Based on the sponsorship letter, the Turkish Embassy in Washington D.C. granted a three-month visa to me and my family.

In the meantime, I had also applied for a fellowship from the American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS) in Chicago to support my field research in India. Thanks to the strong recommendations of Professor Frykenberg and Professor Manendra Varma, Chairman of the Center of South Asian Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the AIIS granted me a Junior Fellowship worth 8,000 rupees per month for ten months, along with a contingency grant of 12,000 rupees.

We decided to visit Istanbul before traveling back to India. In June 1981, we said goodbye to all our friends in Madison and flew to New York, where we were to take a connecting flight to Istanbul.

My time in Madison was a period of intense learning, professional transformation, and deep personal fulfillment. From struggling with the cold to achieving my Ph.D. enrollment and reuniting my family, every challenge paved the way for a greater triumph. The doors to international scholarship were now wide open, and the next steps of my research would take me across two continents, cementing my identity as a historian.

To be continued…

Can’t tell how much I enjoyed reading the whole series…… exploring a world unknown to me till now…….. your hard work, diligence and determination to achieve new goals with each passing day is an example for all of us

Thank you very much, Zeba!