In my previous post, I detailed my intense two-year graduate tenure at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. I recounted the challenge of balancing my studies and a campus job, the sheer joy of Nilofer and Tipu joining me in the U.S., and the critical academic steps I took, including successfully defending my dissertation proposal on Mughal–Ottoman Relations and clearing my preliminary exams. My journey now takes a dramatic turn as I leave the familiar comforts of Madison for a crucial phase of my research: a three-month fellowship in the historic city of Istanbul.

An Adventure Begins in Istanbul

We landed in Istanbul on the evening of May 15, 1981. Before leaving Madison, I had called Mr. Najmuddin, a relative of a Turkish friend I often met at Madison’s Islamic center, and he had graciously promised to receive us at the airport and arrange our initial stay. When we emerged from the airport, we were delighted to find Najmuddin and his friend, Muhammad Ali, who spoke fluent English. Mr. Ahmad Aydin Bolak, my sponsor, had also sent a representative of Indian origin who spoke Urdu to meet us.

Mr. Bolak’s representative informed me that arrangements for our stay in a hotel had already been made and handed me 40,000 liras for our expenses for the rest of June. I profusely thanked Najmuddin and Muhammad Ali for their warm welcome, promising to call them the next day. We then checked into the hotel with Mr. Bolak’s representative, who told me he would return the next morning to take us to meet Mr. Bolak in his office.

Tired from the long flight, we rested briefly before heading to a restaurant across from the hotel for dinner. It was there that an unforgettable incident took place. Nilofer accidentally left her purse behind, which contained our passports, the 40,000 liras, and the $2,000 we had brought with us. Losing a passport in a foreign country is a recipe for disaster, and being left penniless would have been a catastrophe. Fortunately, the waiter who had served us dinner had seen us enter the hotel. He came running after us, shouting Baji (the Turkish word for elder sister), and handed the purse back to Nilofer. I profusely thanked the young man and gave him a suitable reward for his honesty. No words were enough to thank Allah for saving us from such a calamity. Even today, I shiver thinking about what might have happened had that honest boy not seen us enter the hotel.

Unprecedented Generosity

The next morning, we met Mr. Bolak at his office, accompanied by his representative. He received us with great warmth and informed us that he had arranged a house for us to stay in during our entire sojourn in Istanbul. The house belonged to Professor Abdul Qadir Erengul of Istanbul University, a friend of Mr. Bolak, who had gone to stay at his resort on the shores of the Bosphorus for three months. The house was located in the fashionable Teshwique area on Nishantasi Caddesi (road), on the European side of Istanbul—the only city in the world located on two continents. Mr. Bolak also very graciously covered the house rent for the full three months. He then instructed his representative to take me to the National Archives of Turkey, which was located on the Asian side of the city. Mr. Bolak’s generosity toward a stranger like me was unprecedented and truly unparalleled. I was saddened to recently learn that Mr. Bolak passed away in 2019. From that day on, I pray for his maghfirat (forgiveness) every day. May Allah enhance his rank in paradise.

Delving into the Ottoman Archives

The next day, I went to the National Archives of Turkey (Başbakanlık Arşivi / Archives of the Prime Ministry), accompanied by Mr. Bolak’s representative. I met the Director of the Archives, a retired army general, and presented the official letter from the University of Wisconsin–Madison requesting permission to use the archives. Since the Turkish government had already approved my research topic, the Director graciously allowed me to begin my work. I was informed that the archives were open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays, and that I was permitted to photocopy a maximum of one hundred documents relevant to my research.

The National Archives of Turkey is perhaps the richest archive in the world, containing over 150 million documents spanning the history of the Ottoman Empire from the 13th to the early 20th century. The archives had detailed catalogs, which researchers had to consult to locate documents. I quickly found that three sets of records were most likely to yield the information I needed: the Muhimme Defterleri (Registers of Important Affairs), the Namaye Humayun Defterleri (Registers of Imperial Letters), and the Tapu Tehrir Defterleri (Registers of the various sea ports). I also had the pleasure of meeting American, British, and Turkish scholars working there, and was particularly honored to meet the renowned historian Professor Bernard Lewis of Princeton University, who happened to be present that day. I left the archives around 5 p.m., determined to begin working formally the following day.

Settling into City Life

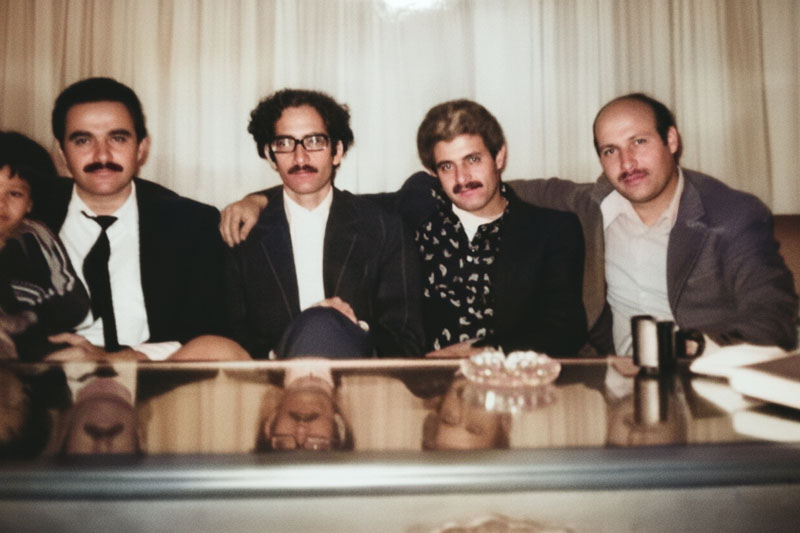

Two days after arriving in Istanbul, we moved out of the hotel and into Professor Erengul’s apartment. Mrs. Erengul was there to welcome us and showed Nilofer how to operate the kitchen stove and the washing machine, assuring us we were free to use all the utensils and crockery. The apartment was fully furnished with two bedrooms, a study room, and even a landline telephone, which we were also allowed to use. I called Najmuddin and Muhammad Ali, sharing our new address and inviting them to visit. They came that evening, helped us buy necessary groceries for the month, and showed me how to reach the archives from the apartment. This marked the beginning of a very close friendship with them and their families. I will forever be grateful for their selfless assistance during our three-month stay.

I started going to the archives the very next day. Our apartment was in a multi-story building with a 24-hour guard, so I didn’t have to worry about the safety of Nilofer and Tipu. I quickly found a shared taxi, called a dolmush, near the apartment that dropped me off within comfortable walking distance of the archives. I soon got used to the working system of the archives, thanks to the gracious staff.

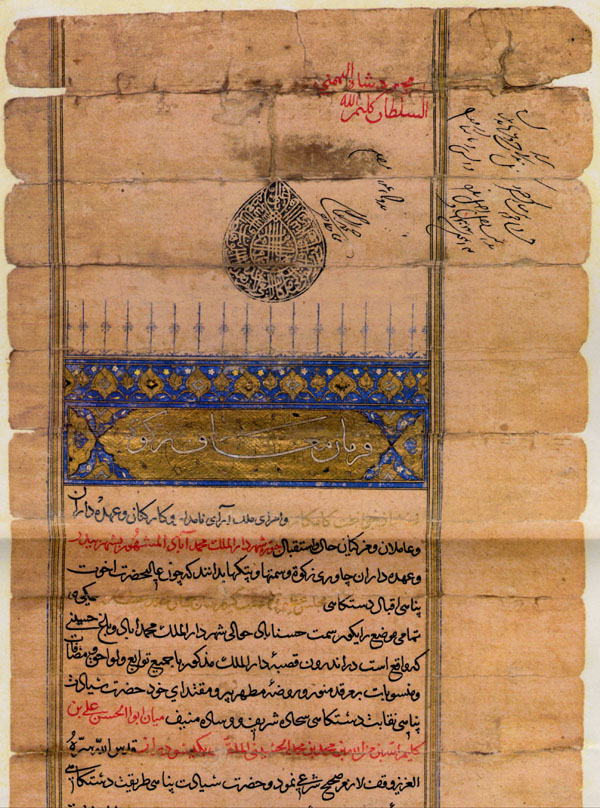

Discovering Historical Gold

I worked tirelessly in the archives for the next three months, uncovering a number of documents previously unknown to Indian historians. In the Muhimme Defterleri, I located several royal farmans (Ottoman Sultan’s orders), including a set of six regarding problems caused by Indian pilgrims accompanying the ladies of Akbar’s harem, and the action taken against them by the Ottoman authorities (I have written about this episode in my earlier blog on the grand Hajj of 1575). I also found farmans detailing the difficulties faced by Indian traders in Ottoman ports, as well as letters from Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566) warning the King of Portugal against harassing pilgrims and traders from India.

One particularly interesting farman revealed the plight of the family of Sultan Bahadur Shah of Gujarat, whose minister had entrusted the family and a vast treasure (equal to several billion dollars today) to the Ottomans before a Portuguese invasion. The Ottoman authorities appropriated the treasure after Bahadur Shah’s death, leaving his family dependent on a state pension. Another farman showed that the Ottoman Sultans were granting one hundred gold coins annually to the Khatibs (Imams) of 27 mosques in Kerala to pray for the well-being of the Ottoman rulers, effectively acknowledging the Sultan as a spiritual overlord.

In the Namaye Humayun Defterleri, I found letters exchanged between the Ottoman Sultans and Indian rulers like Aurangzeb, Farrukhsiyar, Muhammad Shah, the Nizams of Hyderabad, and Tipu Sultan. These Indian letters were written in Persian, while the Ottoman replies were in Turkish. I even found a rare inventory of gifts sent by Muhammad Shah to Sultan Mahmud II, copied in volume seven. The registers also contained letters from Nadir Shah and Ahmad Shah Abdali recounting their Indian campaigns. I was likely the first Indian student to discover these documents. Although the archives limited photocopying to 100 pages, the staff graciously allowed me to photocopy 120 pages, and I copied the rest by hand into two notebooks.

A Glimpse into Royal Archives

Once a week, I also visited the Topkapi Palace Archives, located nearby. Topkapi Palace had been the official residence of the Ottoman Sultans for nearly five centuries. I obtained a daily pass, which allowed me to enter the complex without buying a ticket. Here, I found documents related to the Ottoman campaign against Diu (1538) on the coast of Gujarat, commanded by the Governor of Egypt, Khadim Suleiman Pasha. The campaign failed due to a lack of coordination and ultimately led to Khadim Pasha’s execution by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

I also found a lengthy document titled “The Petition of the Indian Muslims to the Ottoman Sultan.” A close study, however, revealed it was actually a petition from the ruler of Sumatra requesting Ottoman military assistance against the Portuguese. This document also fascinatingly revealed that Muslims in Kerala, Ceylon, Maldives, and Sumatra read the khutba (Friday sermon) in the name of the Ottoman Sultan, virtually acknowledging him as their sovereign. Since I was not allowed to get a photocopy of this petition, I had to copy it by hand, which took several days.

The Splendor of Istanbul

Istanbul is a large, vibrant, and crowded city, much like Bombay or New Delhi. The city’s skyline is famously dotted with magnificent monuments, especially the grand mosques built by the Ottoman Sultans, attracting millions of tourists annually. Every weekend, our Turkish friend Muhammad Ali kindly took us around the city. We can never forget his generosity in showing us the sights; he also became very fond of Tipu and constantly tried to please him.

We visited the Topkapi Palace, which had been converted into a museum after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. The museum is, without exaggeration, one of the most fabulous and richest in the world. Its main attraction is the tabarrukat (sacred relics), including the staff, bow, and clothing of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), and the swords of the Khulafaur Rashidin (the first four Caliphs). Also on display is the Holy Quran being read by the third Caliph, Hazrat Usman, at the time of his assassination. The museum boasts the world’s largest collection of Chinese porcelains, gifted by Chinese monarchs, as well as a fabulous collection of Islamic calligraphy. It also houses gifts sent by Nadir Shah after his Indian campaign, including a throne of pure pearls looted from the Red Fort and the famous diamond-embedded Topkapi Dagger.

We also visited the Hagia Sophia, once regarded as the largest church in the world, built by Constantine the Great, which was converted into a mosque by Sultan Muhammad II after he conquered Constantinople (and renamed it Istanbul) in 1453. We saw the colossal Suleymaniye Mosque, built by Suleiman the Magnificent, and the beautiful Blue Mosque, built by Sultan Ahmed I in 1617. The mosque complex housing the tomb of Sultan Muhammad II also impressed us greatly. The tomb of Hazrat Abu Ayub Ansari, a companion of Prophet Muhammad, is a sacred place miraculously discovered after the conquest of Istanbul, and a must-visit for every Muslim tourist.

Our stay in Istanbul was both delightful and a great learning experience. We enjoyed the generous hospitality of the families of Muhammad Ali and Najmuddin and hosted them for dinner at our residence. I even invited my fellow American and British scholars from the National Archives for a dinner. We celebrated the holy month of Ramadan and Eid in Istanbul, experiencing the joy of these festivals in a truly Islamic environment. We also became very fond of Turkish cuisine, especially the meat dishes, kebabs, and baklava.

This three-month fellowship in Istanbul was more than just a research trip; it was a deeply enriching cultural and personal immersion. The unparalleled generosity of the Turkish people and the historical gold I discovered in the archives cemented the foundations of my doctoral work. Having completed this crucial phase, I was now prepared to return to India to conclude my field research before embarking on the final writing phase of my dissertation.

To be continued…

Amazing learning experience an eye opener wtite up. No words to thank for such powerful experience and knowing about Turkey and Turkish treasure and people of Turkey.

Thank you so much, Arshad!