In the last part of my story, I detailed my intense two-year graduate tenure at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, culminating in securing my Ph.D. enrollment and undertaking a three-month research fellowship in Istanbul. That chapter ended with Nilofer, Tipu, and me saying tearful goodbyes to our generous Turkish friends as we prepared to fly back to India. Now, in this seventh installment, I recount my return home, the completion of my critical field research in India, and the significant effort required to secure a path back to the United States to finish my dissertation.

Returning Home to Resume Research

Alas, our stay in Istanbul came to an end in August 1981. With the help of Muhammad Ali, I booked our return flight to New Delhi via Dubai by Turkish Airlines. We flew to our destination on August 14, 1981, with tears in our eyes as we parted with dear friends like Muhammad Ali and Najmuddin, who had come to bid us farewell at the airport. I remain eternally indebted to them for their love, kindness, and generosity, which made our stay in Istanbul smooth and trouble-free.

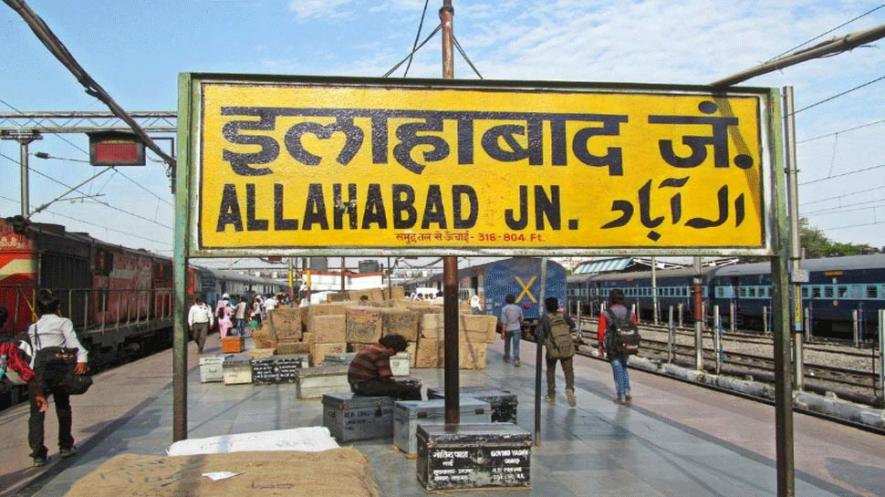

We landed at Delhi’s Palam airport the next morning. My brother Bhaiyya (May Allah enhance his rank in paradise) was kind enough to receive us and drove us to his home in Kaka Nagar. That same night, we caught the train to Allahabad, reaching home on the morning of August 15, 1981. It was a sheer joy to meet my revered mother, Kalim, and my other siblings after a gap of three years.

The next day, I went to the university and immediately rejoined my duties in the Department of Mediaeval and Modern History. After a few days, I traveled to Benaras to meet the Director of the India office of the American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS). The Director informed me that the distinguished historian Professor Khaliq Ahmad Nizami of Aligarh Muslim University had been appointed as my local supervisor. I was advised to meet him as soon as possible. When the Director learned that I had resumed my teaching duties at the university, he informed me that I was not permitted to receive the AIIS fellowship while holding a teaching position. He strongly advised me to take leave from the university forthwith.

Returning to Allahabad, I shared my predicament with the head of the department, Professor C.B. Tripathi. He advised me to apply for nine months’ leave and was gracious enough to strongly recommend my application to the Vice Chancellor. My application was approved in due course, and I became ready to embark upon my crucial field research in India.

Working with Professor Nizami

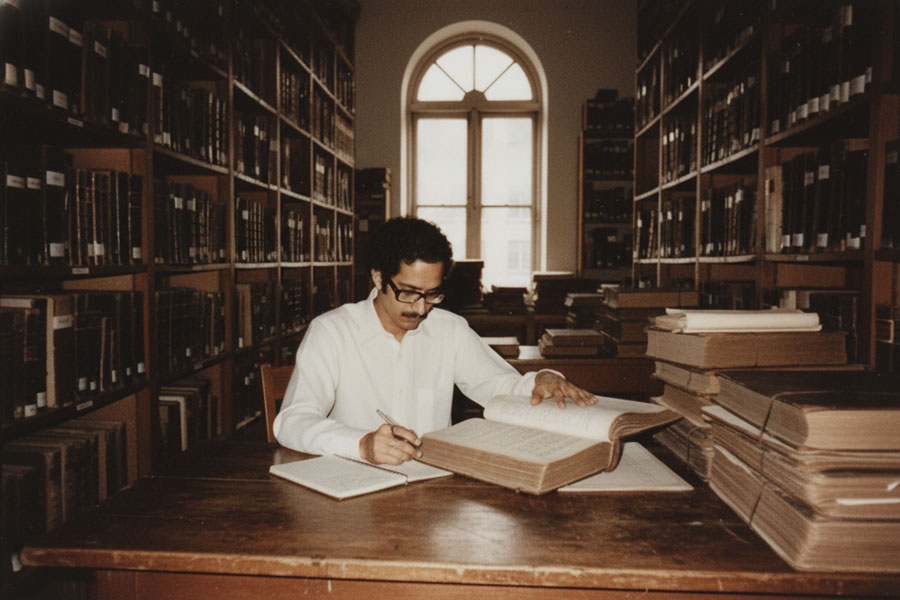

The next week, I traveled to Aligarh to meet Professor Nizami. He received me cordially and introduced me to the other research scholars in the department. He invited me to attend the weekly meeting of research scholars scheduled for that evening. After the meeting, he discussed the specific issues related to my research topic. He was of the opinion that I should visit Aligarh frequently to use the material available in the seminar library of the History department and the Maulana Azad Library. He also suggested I visit Bombay and Goa to explore the valuable documents available in their respective archives. I stayed in Aligarh for a few days, where I had the privilege of meeting distinguished historians like Professors Irfan Habib, Athar Ali, Iqtidar Alam Khan, and Ahsan Jan Qaisar, with whom I discussed the best way to proceed with my research project. I also befriended Dr. Ishtiyaq Ahmad Zilli, Iqbal Hussain, and Afzal Hussain, assistant professors in the department, who would become lifelong friends.

Unearthing Records in Bombay

Returning to Allahabad, I planned my first research trip to Bombay in October 1981 to explore the material available in the Maharashtra State Archives. This visit was greatly facilitated by the courtesy of my brother Bhaiyya, who arranged for my stay in a post office guest house almost adjacent to Dadar railway station.

The archives itself was situated within the complex of the Elphinstone College, about 10 km from Dadar station. Reaching the archives from there proved to be a tough endeavor. I initially tried to travel by public transport—roadways bus and the local train—but after a few days, I realized that traveling by the crowded public system was beyond my capacity to endure. I therefore began to travel by auto-rickshaw (three-wheeler).

The Maharashtra State Archives was a treasure house of English factory records from Bombay and other cities where the British had established their presence in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The archives staff was extremely helpful and cooperative in locating records that would be fruitful for my research. The factory records were preserved in huge, bulky registers, each weighing at least 10 to 15 kilograms. I consulted several volumes of the Surat Factory records, the Surat Factory Outward Letter Book, Mokha Factory diary, Basra Factory Outward Letter Book, Secretariat Outward Letter Book, Secretariat Inward Letter Book, and Selections of papers received from India Office. Since it was virtually impossible to photocopy the documents from those massive registers, I had to copy them painstakingly by hand, which took me more than two weeks. My task remained incomplete, and I returned to Allahabad resolving to return to Bombay again.

Aligarh Revisited and a New Arrival

I traveled to Aligarh again in November, and with Professor Nizami’s permission, I spent several days thoroughly exploring the History department’s seminar library. It was there that I found Ahmad Faridun Bey’s Munshat al Salatin, a collection of letters written and received by the Ottoman Sultans. In this invaluable book, I found letters exchanged between the Bahmani and Gujarati Sultans and the Ottomans. Crucially, I also found several letters exchanged between Jahangir and Shahjahan and their contemporary Ottoman Sultans, along with a letter from Prince Dara Shukoh. As was typical, the letters written by the Indian monarchs were in Persian, while the replies were composed in Turkish. I made sure to get photocopies of all these letters. The Maulana Azad Library, however, did not yield any significant material for my subject. During my frequent visits to the History department, I became very friendly with Inayat Zaidi, Sunita (who later married each other), Ahmad Khan, and others. My university fellow Anwarul Haque was also enrolled there in the Ph.D. program, and discussing our common academic problems with them was a sheer joy. After staying at Aligarh for two weeks, I returned to Allahabad.

The year 1982 began with an overwhelming joy and happiness with the arrival of a new member in our family. On January 24, 1982, Khurram was born at the Allahabad Nursing Home. His arrival brought untold bliss and delight for us. Being a history student, I was looking for a suitable historical name for him. We therefore named him Khurram, the future Shahjahan, which means joy and cheerfulness. Khurram was such a happy and beautiful child that my brother Muhammad Ahmed Bhai always kept his picture in his wallet. Young Tipu became very fond of his little brother and looked after him with great love and care.

The Final Stretch of Indian Research

In May 1982, I decided it was time to visit Bombay and Goa to complete my unfinished research. This time, Nilofer, Tipu, and Khurram also accompanied me. We stayed at the Dadar post office guest house for one week. I visited the Maharashtra State Archives every day, and with the help of the staff, I managed to copy some more relevant documents from the English factory records.

After a week, we left for Goa by night bus, reaching Panaji in the early morning. Thanks to the post office staff in Bombay, we had already rented a house in Panaji and settled there for a few days. We didn’t relish the food served in Panaji’s restaurants, so we borrowed a few utensils and an electric stove from the landlord, and Nilofer cooked simple, much-needed home food for us.

A few days later, I had a chance meeting with an old university friend, Anis Farooqi, in a mosque after the Friday prayer. He was working as a scientist in the National Physical Laboratory there. He immediately invited us to stay in the Laboratory’s guest house, and we moved there that same day.

From day one, I had been visiting the Historical Archives of Goa, traveling there by paying five rupees one way to the available motorcycle riders. The archives staff was very courteous and helpful. With their assistance, I found that the documents useful for my subject could be located in the series known as Consultas do Servico do Partes. Naturally, these documents were in Portuguese, which was like Greek and Latin to me. However, with the help of the staff, I found a few documents in the third volume of this series that shed light on the Ottoman–Portuguese relations. Fortunately, English summaries of these documents were appended to the original copies in the register. I immediately got photocopies of the English summaries and thanked my luck. On the weekend, we took a guided bus tour of Panaji, visiting the world-renowned beaches and historical monuments, including the fort and the central church built by the Portuguese. Since Khurram was only four months old, we bought a child trolley to carry him around. After a stay of almost ten days in Panaji, we returned to Bombay and from there, boarded the train for Allahabad.

The Persistent Push to Return to Madison

In June 1982, my AIIS fellowship came to an end, and I rejoined my duties at the university. Over the last ten months, I had worked diligently to utilize the fellowship grant. I used the contingency grant to pay for the railway fares for visiting Aligarh, Bombay, and Goa, and I spent a significant portion of the stipend to buy several books needed for my research. I also used a good amount of my monthly stipend and savings to repair and refurbish our house in Rajapur.

Professor Tripathi once again assigned me to teach American History to postgraduate students, alongside my other classes. The department had seen many new faculty members join, including V.C. Pande, who had returned from Bristol, U.K.; Sushil Srivastava; Mrs. Uma Rao; Dr. Mrs. Ranjana Kakkar from JNU; and my former students P.L. Vishwakarma, Heramb Chaturvedi, and Lalit Joshi. We worked together harmoniously under the inspiring leadership of Professor Tripathi. My friend, Syed Najmul Raza Rivi, whom I had first met in a refresher course in AMU in 1977, had also joined the department as a Ph.D. scholar from his college in Tanda under the UGC’s Faculty Development program.

All this time, I was also actively planning to return to the USA to write and submit my Ph.D. dissertation. However, securing a U.S. visa for myself and my family presented many unforeseen problems. In May 1982, my visa application was rejected by the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi due to a lack of sufficient demonstrated financial assistance. I was told I could reapply only after six months.

Continuing my enrollment in the doctoral program at Madison was also a major concern. After clearing the preliminary examination, my tuition fees had been reduced to just $250 per semester, which was barely ten percent of the normal fee. Before leaving Madison, I had given $500 to my friend Amanullah Khan saheb to deposit my tuition fees for two semesters, hoping we would return within a year. I shared my current problem with Aman Saheb, and he very graciously agreed to deposit my fees every semester, pending my return to Madison.

In the meanwhile, we had admitted Tipu to a play school named Green Lawns, not far from our house in Rajapur. In July 1982, we admitted him to the Boys’ High School, a reputed English medium public school, in the first standard. I continued teaching at the university with full vigor while trying my level best to somehow get back to Madison.

Professor Frykenberg was equally keen to have me back in the USA as soon as possible. He successfully persuaded the Center for South Asian Studies to consider me for a temporary lecturership for two semesters. In March 1983, I received an official letter from the Center’s Chairman offering me a lecturer’s job at a salary of $500 per month for two semesters, starting September 1983. However, this amount was not quite enough to secure a visa for a family of four.

At this critical point, my brother Bhaiya’s friend, Tufail Saheb, a businessman in Washington D.C., came to my rescue. In June 1983, he sent a letter addressed to the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi stating his willingness to sponsor our visit to the U.S., guaranteeing he would take care of our expenses during our stay in Madison. Although I never needed his financial assistance eventually, this document proved to be a great help in getting the job done, and we immediately began preparations for traveling to the U.S.

In April 1983, Kalim was married to Rana Syed, the daughter of Syed Tasadduq Hussain. Her arrival as a new member of the family was a source of joy for all of us. I was also happy that during our absence from Allahabad, she would be there to help and keep company with my mother.

In August 1983, we traveled to New Delhi to apply for the U.S. visa. By the grace of Allah, on the strength of the official job letter and Tufail Saheb’s sponsorship, our visa application was approved this time. Saeed’s mother, Nurussaba Bhabi, had also applied for a U.S. visa, and her application was approved as well. We planned to travel together to the USA. I booked tickets for all four of us for the New Delhi–Chicago flight, using my savings from my university salary and the AIIS fellowship. I also applied for one year’s leave without pay from the university. With Professor Tripathi’s strong recommendation, the university agreed to grant the leave. Immediately after procuring the visa, I wrote to the authorities of the University Housing scheme, requesting the allotment of a two-bedroom flat in the Eagle Heights colony. They promptly replied that flat number 301-F had been allotted to me, effective September 1, 1983. On September 5, we bid a tearful farewell to my revered mother and traveled to New Delhi by the night train for our onward journey to Chicago. The next night, accompanied by Nurussaba Bhabi, we flew to Chicago.

My return to India was a whirlwind of intense research, personal celebration, and the frustrating bureaucratic struggle to return to Madison. The unwavering support of my professors, brothers, and friends—combined with Nilofer’s quiet strength and the joy of our children—made the impossible possible. With a job offer and a visa finally in hand, I was ready to complete the final, most crucial phase of my doctoral journey and fulfill the promise of my Fulbright scholarship.

To be continued…

Truly inspirational journey 👏

Thank you very much!

As usual enjoyed this part 7 and waiting for more